By John Corrado

There’s this idea introduced at the start of director Ryan Coogler’s Sinners about how every culture has a different word for people who can play music so powerful that it can transcend spirit worlds and “pierce the veil” between the living and the dead.

There’s this idea introduced at the start of director Ryan Coogler’s Sinners about how every culture has a different word for people who can play music so powerful that it can transcend spirit worlds and “pierce the veil” between the living and the dead.

It’s a theme that is prevalent throughout Blues music (i.e., “Devil Went Down to Georgia”) and is embedded in the genre itself, stemming from the mythos of Blues legend Robert Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the Mississippi crossroads in order to be able to play.

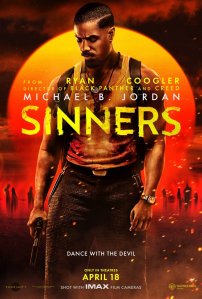

Sinners finds Coogler building on the promise that he showed in Creed and the Black Panther movies to craft an original film, his first since his 2013 debut Fruitvale Station. Freed from any franchise constraints – yet afforded the trust to work with a massive studio budget – Coogler delivers an ambitious, wholly original blockbuster that seamlessly melds 1930s period drama with vampire horror.

It’s an incredibly well-crafted, gorgeously shot genre blend. But the most thrilling aspect of Sinners is how Coogler incorporates the musical elements into the film. He builds a story around the rich history of African-American contributions to music, namely the Delta Blues. Coogler himself is working like a musician in the ways that he seamlessly blends and melds genre elements into the story, one that is still rooted in its characters and history.

But music is what ties it all together, including an absolute knockout score from composer Ludwig Göransson. Göransson is one of Coogler’s frequent collaborators, having won his first Oscar for Black Panther (and his second for Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer). His work here, which heavily features slide guitar and pays tribute to the music of the era while also ingeniously incorporating modern elements, works perfectly in harmony with Coogler’s vision, and is like a character unto itself.

The film stars Michael B. Jordan – another one of Coogler’s go-to collaborators – in the dual role of twin brothers Elijah and Elias Moore. The story begins with the brothers rolling back into their hometown of Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1932 after spending several years in Chicago, where it’s suggested they hit it rich working for Al Capone. They have blood money to spend that they use to purchase the old sawmill, which will be transformed it into their own juke joint.

The first stretch of Sinners follows the Moore brothers as they prepare for the grand opening that night. They reconnect with figures from their past, who they cajole into working or performing at the new club. First up is their younger cousin Sammie (Miles Caton), a preternaturally talented aspiring Blues guitarist who has the nickname “Preacher Boy” due to being the son of the local pastor. There’s Elijah’s estranged wife Annie (Wunmi Mosaku), and Elias’s old flame Mary (Hailee Steinfeld).

They also recruit Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo), an aging, alcoholic musician who is reluctant to give up his steady, reliable gigs at the local hangout. But the brothers offer him more money than he currently makes. This theme of transactions, money changing hands, and offering people what they are worth, threads throughout the film. The trauma and history of slavery looms large over this story and town, with many of the peripheral characters working the plantations.

The first half of Coogler’s film is a slow burn; it’s all about the build up, the anticipation of what is to come. Coogler plays with tension and release, like a musician building to a solo (or, more explicitly, in the sexual scenes, with the film eschewing a sort of sweaty sensuality). The genre elements, when they do present themselves, work because of Coogler’s careful buildup, and the ways he establishes this world and sets up each of these characters at this specific moment in time. This includes a villain, Remmick (Jack O’Connell), who emerges from the shadows.

Coogler is working with many of his frequent collaborators. The production design (by Black Panther Oscar-winner Hannah Beachler) and costumes (by fellow Black Panther Oscar-winner Ruth E. Carter) immerse us in the world of Mississippi circa the 1930s. Shot on 65mm film, the cinematography by Autumn Durald Arkapaw (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever) features striking, ultra-widescreen images, presented in a glorious 2.76:1 aspect ratio.

At 138 minutes, the film moves; editor Michael P. Shawver, who also cut Coogler’s four previous films, keeps the story flowing, cutting between sequences and scenes. The strong performances from the entire ensemble make each of the characters feel alive. Jordan delivers an excellent dual performance that allows both brothers to feel distinct. Caton feels like a star in the making, especially in soaring musical moments, while screen veteran Lindo steals every scene. Then there’s O’Connell, whose Remmick is a chilling, fascinating villain who is captivating to watch. And the list goes on.

Coogler’s screenplay is rich with symbolism and meaning about the African-American experience in the Jim Crow South, and the role music plays in shaping culture. The film is so dense with themes that a second viewing is likely required to absorb everything. For example, it’s more debatable exactly what the film is trying to say about Irish immigrants who came over and faced immense hardships before assimilating. Finally, the choice to present the epilogue as a mid-credits scene also doesn’t quite work. It leaves the scene itself – which is, in many ways, the emotional coda – feeling slightly separate from the film.

But Sinners often astounds – even overwhelms, in the best way – on a purely sensory, cinematic level. Coogler flexes his directorial muscles throughout, with several standout set-pieces that allow him to show off his filmmaking prowess. The best of which is when Caton’s Preacher Boy finally takes centre stage partway through, and plays something that helps the film transcend to even greater heights, through a swirling, single-take sequence. It’s in keeping with that theme about the Blues having the ability to connect us to something higher – beyond past, present and future, or genre – which is when Sinners is at its best.