By John Corrado

Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” (those quotation marks are an intentional stylistic choice) is the Promising Young Woman and Saltburn filmmaker’s take on the classic Emily Brontë novel from the 1840s.

Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights” (those quotation marks are an intentional stylistic choice) is the Promising Young Woman and Saltburn filmmaker’s take on the classic Emily Brontë novel from the 1840s.

Fennell’s adaptation is a mildly revisionist and risqué take on Brontë. This is her version of Catherine Earnshaw and Heathcliff’s doomed love story, built around how she imagines these characters. The result is a film of big feelings and sweeping, swooning emotion, one that embraces being a classic cinematic melodrama.

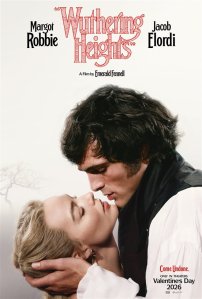

Cathy and Heathcliff are played in this version by Australian actors Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi, with the film largely playing off of the intense chemistry between them. The film opens with the characters as children.

Young Cathy (played by Charlotte Mellington) first meets young Heathcliff (award-winning Adolescence actor Owen Cooper), when Cathy’s father (Martin Clunes) brings the boy into their home. Heathcliff – whom she names – becomes both servant and companion to Cathy. The two form a close bond over the years as they grow up together, into the adult versions portrayed by Robbie and Elordi, but a misunderstanding ends up pulling them apart.

The film does take its share of liberties with Brontë’s original text, but it’s not intended necessarily as a literal adaptation and more as a reimagining (again, think of those quotation marks). Fennell has said that she wanted to make the version of Wuthering Heights that she imagined when she first read the novel at fourteen years old, and that is an interesting way of approaching the film.

This is Brontë, but noticeably also a film from the same director as Saltburn and Promising Young Woman. Like Saltburn, Fennell’s previous collaboration with Elordi, “Wuthering Heights” can feel a little tawdry in places, even if the film as a whole teeters between being provocative and not nearly as scandalous as it thinks it is (there is no actual nudity). But this adaptation still gets pretty hot and heavy at times with moments of abject horniness (for lack of a better word), including a steamy sex montage designed to make the purists blush. In this version, Heathcliff is less out of control brute, and more kinky fetishist.

First and foremost, “Wuthering Heights” is a beautiful looking film, that finds Fennell playing around with classical style. Aside from the two leads, the other big selling point are the gorgeous costumes by Oscar-winner Jacqueline Durran (Anna Karenina, Little Women). Durran, who also dressed Robbie in Barbie, delivers a dazzling array of gowns for Cathy to wear, each more impressive and eye-popping than the last.

The production design by Oscar-nominated Suzie Davies (Conclave, Saltburn) also draws us in, from the shadowy interiors of Cathy’s family home in the moors, to the opulent, vibrantly coloured rooms of the manor that she moves into with Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif). One moment in particular stands out when the image cross-fades into an elaborate dollhouse of the same room.

It’s all captured by Linus Sandgren’s lush cinematography, with magic hour shots of Elordi’s Heathcliff on horseback, or riding through thick fog, that are meant to evoke Gone With the Wind. The elements play a huge role here, with the rainy, windswept moors and rocky cliffs providing a moody, gothic backdrop for key scenes. There is a wonderful texture to the images, with Sandgren shooting on 35mm film.

It’s a period piece cut from a similar cloth as Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette or Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby. Most notably, in keeping with the anachronisms of those films’ now-iconic soundtracks, “Wuthering Heights” includes a selection of new Charli XCX songs that work surprisingly well in context. This is Charli XCX at her most brooding, matching the heightened style of the film.

The main selling point is the chemistry between Robbie and Elordi, two conventionally attractive (read: hot) actors whom audiences of any orientation can take pleasure in watching onscreen. Elordi undergoes a transformation from a more feral-looking Heathcliff with his shaggy hair and beard into a cleaned up gentleman, that Fennell frames as a particularly swoon-worthy moment. Again, think of this as teenaged Fennell’s imagined version of Heathcliff, like her own Jack from Titanic.

The other two performances that bring a lot to the film are Hong Chau as Cathy’s personal servant Nelly Dean, and Alison Oliver as Edgar’s sister Isabella Linton, who both bring added layers to their portrayals. Oliver steals scenes as the eccentric (and very kinky) Isabella, while Chau plays Nelly as someone who keeps her cards close to her chest, leaving us questioning if she is protecting Cathy or sabotaging her.

It is best to approach “Wuthering Heights” from within those quotation marks as a new imagining of Brontë’s novel. It works as a classic period romance, but one that is channeled through Fennell’s own sensibilities. It’s a marriage of material and directorial style that will prove divisive, but also reaps some visually sumptuous cinematic pleasures and heightened emotional payoffs. I was personally quite swept up by the whole thing.